Ruth and Lauren reflect on their Remix Residency

One morning in February, Lauren was doing her usual aimless morning scroll through instagram. As she was flicking past all of her cats with hats accounts and insta feminist quotes, she noticed that Talking Birds had made a call out for the Remix Residency at The Nest. She saw a huge variety of props in a picture and was drawn in immediately. There was something about that telephone, that explorers hat! The bucket and spade. It sparked off ideas which started to whirl through her brain, so she messaged Izzy and Ruth.

“I think we may have a shot at this!’

Fast forward to a week later in Gails Balham (a local haunt of ours) Ruth and Lauren discussed ideas that were stimulated from the picture. Coventry’s female and industrial history, the idea of legacy, what Coventry means to us. What would happen if we created a dystopian world filled with time travel, with women at the core? These were just a few topics that we indulged in. We knew we wanted movement at the heart, with small pieces of text to lead the story forwards. Pumped up from all of these tangible ideas, we set to work applying for it. Janet saw something in these mini moments we had created and would you believe it, we were accepted! Now the real work begins…

Before we knew it we arrived in Coventry for our first section of the Residency. It was a lovely sunny day in May. Lauren and Ruth entered the bright blue gates of Sandy Lane Business Park. We began our work in ‘The Space Of Possibilities’ room in The Nest. It was bright and spacious, with so much room for us to create. Within minutes we knew we would feel very comfortable in this space. It felt like our little home for the week.

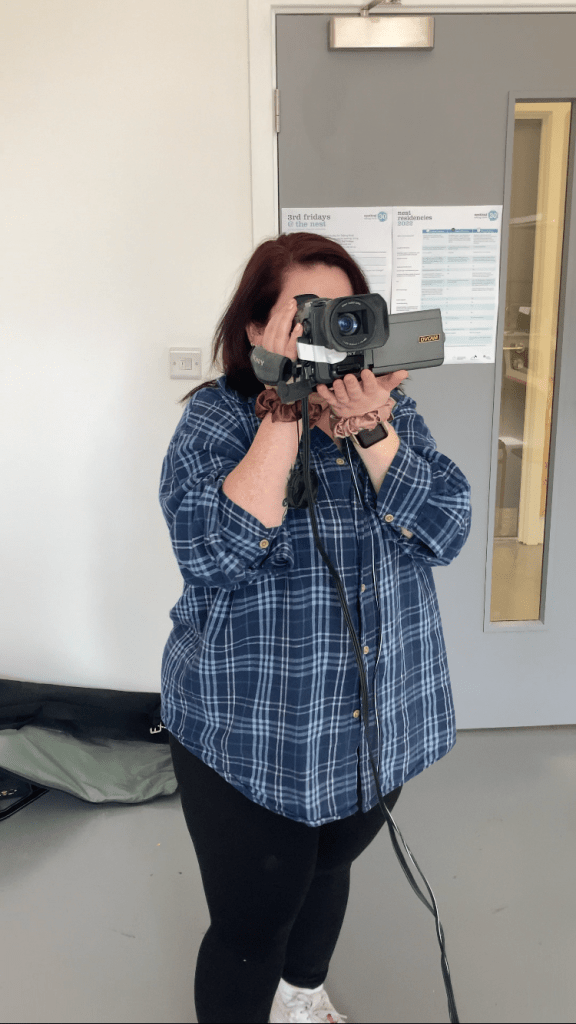

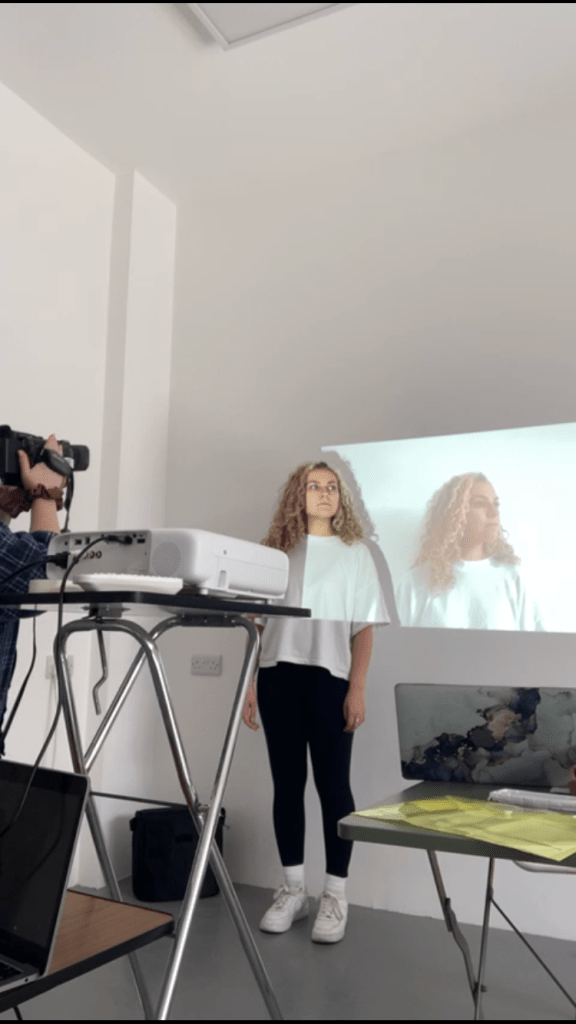

For the first week we just allowed ourselves to play (something which feels so rare in this industry!) The pressure was completely off, so we messed around with tech we’ve wanted to work with for years. Trying out different ways we can use projection, live camera feed and sound. It began to spark so many new ideas for what this project could be. We tested an idea (which came from the projection) about the audience’s perception. What would happen if we projected an image onto the umbrella, but behind it was something completely different? Or a different part of the story being told? We found a bit of magic in this idea, so we ran with it.

Our next stage was to figure out what story we wanted to create. We knew we wanted it to be about Women of Coventry and the stories that seem to be forgotten. We’ve all heard of Lady Godiva, but who else gets to be or should be just as iconic? And you know what, we just couldn’t think. We couldn’t think of any other woman who is allowed to be a figurehead like she is.

So we took to our laptops and began our research. Straight away a name popped up, a woman called Alice Arnold. The first ever female Mayor in England. We couldn’t believe it.

The more we researched her, the more we fell in love with her story. She felt so real to us. Even though she was born in 1880, Alice felt like a modern woman. With real hopes and dreams. Her progressive views and big dreams for gender equality, education and to end poverty just proves that she’s the kind of woman we’d love.

The next woman we researched was a little closer to home and more of a household name. Pauline Black. Visually recognised for her androgenous style, she was a woman we wanted to know more about. Hailed as the Queen of Ska, Pauline became an icon of her music genre. And of course, she is the lead singer of the band The Selecter. Black has also been an actress, with roles in films and television.

Our research came to an end when we found our third female story. Lisa Lashes. Known for being a hell raiser in the rave scene in the 90’s, Lisa was one of the first female DJ’s to break out of Coventry. We loved these women so much already.

We flung post-it notes on the walls of the room, scribbling down our findings and our ever growing questions. The room felt mighty. We were both fueled up with these stories. We played Lisa and Pauline’s music and filled the room with their words and beats. Messing around with movement and tech, we began to create a rough structure for the world we wanted to create.

In our second section of the residency, we introduced two ensemble members to the room. Julia and Sinéad. We wanted their role in this section to enhance our findings and embody some of our ideas further. Extra bodies in the room are always great for storytelling. Oh and for games. Grandma’s footsteps just doesn’t do itself justice with only two players. And we’re super competitive. (Ask Julia and Sinéad).

Over the next few days, we set to work discussing some themes we wanted to work with and some free writing tasks.

‘When I think of Coventry I think of…’

‘A woman can be…’

‘Home means to me…’

‘To f*ck with form you have to…’

These were a few of our free writing starting points. From this, we began to create small pieces of movement involving the props given to us. We all chose two items from the prop box, a section of our writing and 8 movements to create mini pieces. We then watched and gave feedback on moments we’d love to push more. As Ruth is a Movement Director, she then cast her eye over the work we had made. Ruth pushed us for more ensemble moments and different ways Lauren, Julia and Sinéad could connect.

It was such an eye opening exercise. We really felt each other’s warmth in the room, as cliché as that is to say. Hearing different points of view on the city, on what it means to be a woman. It was lush.

Ruth and Lauren then put their heads together at the end of this phase to figure out how we wanted to tell this story. With some time in between, we allowed some dust to settle and to search for the core of it. Tuesday of our final week Ruth and Lauren looked back over bits of writing, videos and also came back to our key themes. And then a line from Sinéad’s free writing drifting into our memory.

“Dreaming alone isn’t enough”

By this point we had learnt so much about these women and we had celebrated their amazing triumphs. But it dawned on us, they’re the first women in their field. They’re singular.

To be honest we feel in history, and the systems that inform it, we often only allow one woman to be held up high and remembered. Like Lady Godiva on the horse “there is space for us all” so why do these women feel isolated? This pushed us to think about the arc of the show. What would happen if the camera and projection only showed one of the performers, not them all. Would it feel more invasive?

We had been playing with video and the camera throughout the process and we wanted to challenge ourselves as a company this week. To move past ‘it looks cool’ or it allows us to play with space. We always knew that the camera felt like it represented much more than just a piece of tech. So we decided to give it a role. We cast it as History.

These were pretty big ideas so we got stuck in practically, pulling together bits of our writing, research and improvisation to make a draft script that we worked on for the next day. Then, Izzy joined us! All of the ideas rattling around Ruth and Lauren’s brain finally had a fresh pair of eyes. Then it was about getting it up on its feet. Sculpting moments through improv, discussion, exercises and best of all collaboration.

On the last day of the residency, we shared our 20 minute piece with some of the Talking Birds team and community. We had a small Q&A at the end and got to hear what resonated, what people felt and thought.

This residency has allowed us to grow as a company. By meeting new people, involving collaborators and working with tech from the seed of an idea. But most of all, giving us the space and support to play. We have continued to learn about our methods as a company and as individual artists. All whilst keeping the core of SpeakUp shining bright at the centre of the work, amplifying untold stories.

We had such an absolute blast, thank you for having us, Talking Birds!

SpeakUp Theatre x