[Long Read] Co-AD Janet reflects on her participation in DutchCulture’s International Visitor’s Programme exploring Regeneration in Arts and Culture.

My first garden in Amsterdam is the one outside my hotel window.

I’m on the third floor and there is the crown of a mature birch tree at the centre of my view: dark, delicate arches of witches-broom twigs with small golden yellow leaves back-lit by pinky morning sun. There’s a wren – that I can’t see – singing its heart out and, every so often, a trio of squawking green necked parakeets sail over.

Just being here feels like such a precious gift, and so unexpected. Somehow, the regenerative work we are trying to do here at The Nest in Coventry has been noticed and I have been invited to the Netherlands: to join an International Visitors Programme centred on Regenerative Arts and Culture together with four other mid-career women engaged in running ecological arts and cultural spaces. Somehow – wonderfully – I feel 10 years of retraction, of inwards-shrinking loops of Brexit-Covid-City-of-Culture-Cost-of-Living-Climate-Crisis, momentarily fold in on themselves, and I step back into Europe more whole, less apologetic: regenerated.

It is my first time in Amsterdam. So much water. So many people. I have the luxury of two days here before the programme begins. Two days to explore, to ground myself, to get the measure of the place. There are galleries and museums galore, but it is the gardens I seek out – of course it is. Orienting myself on foot, by way of plants, and birds, that look, and sound, familiar – recognisable yet not exactly the same; and looking over both shoulders at every junction as I’ve no sense, yet, of where to expect a flurry of bikes or a tram to appear from next.

It is Sunday, and the sun is shining. I head first to Westerpark because, a very long time ago, maybe 25 years back, I heard someone at a conference speak about the Westergasfabriek in Amsterdam – a former industrial site, then in the process of becoming a park. They spoke about how the gas storage tower was turned over to artists to do stuff there, to find out what the space might be good at, in order to inform how it might be developed in future. That stayed with me – allowing the site some agency – working with it to find out what it does well, rather than deciding for it. Like the way wood or stone carvers speak about the material showing them the form it wishes to take as they work it, or gardeners listening to what the soil needs by noting what grows well there.

Luckily the gasfabriek building itself wasn’t open, so my vision of it couldn’t be crushed by the inevitable commercial reality. Next to it is a beautiful, still, reed-filled pool, encircled by brick walls and a boardwalk, which I share with a couple of moorhens. Looping round Westerpark, I peer over at the TuinPark Sloterdijkermeer – like an island of allotment plots with summerhouses; plotholder’s wheelbarrows chained to the bike racks next to the parking spaces outside the main gates. I wish for a moment it was earlier in the year, so that the gates would be open and I could explore inside.

Walking back into the city centre, I’m looking out for examples of Tegelwippen (tile whipping): beautifying and greening the city, providing street cooling, making habitats for insects and birds and opportunities for neighbours to connect and work together – all backed by the buy-in from the authorities. It is the simplicity of the idea that I love – gamifying the greening of urban spaces – as neighbours, neighbourhoods and cities compete to remove the most paving slabs, tiles or tarmac, and replace it with planting. It’s a perfect low-cost, high-impact, regenerative, nature-based climate action, and I’d love to get this happening in Coventry!

It’s not easy to spot which street interventions are actually a result of the Tegelwippen competition, (though there are many that could be) but it certainly feels like there is a different culture around the ownership of, and responsibility to, public space here. As I walk round it seems, wonderfully, that a council worker with a weedkiller backpack could never even exist here. Where there is less traffic, moss and grass grow between the cobbles and slabs, blurring ownership, civic responsibility and notions of ‘neatness’ or control. Outside most front doors are benches, thin slivers of planting with trees and very mature plants right next to the walls, jumbles of pots full of healthy plants…this speaks of care to me: I know how quickly pots dry out. Even the tiniest space seems to be planted, cared for. These streets are dynamic – they suggest agency, connection, community, trust – busy evenings where people sit out and chat, tending to their plants and each other, sharing the stewardship of the rewilded streetscape, and I yearn to live in that kind of a reality.

Monday, I walk east to the University science park to visit Anna’s Tuin & Ruigte (Garden & Wilderness), a community permaculture garden with an educational remit. The information board at the start sets the scene in a way that slightly blows my mind: “You are standing here at 4.5 metres below sea level. This piece of land was once the bottom of the Diemermeer, a lake which was drained in 1629 and its fertile soil was then used for farming.” I am struck again by how water is ever-present here in ways which are both surprising and mundane – aware of the water inside every part of me connecting to the water within the soil, the plants and the canals.

The Tuin & Ruigte is a beautiful space: paths weave through willows and reeds, opening out into a practical composting area and then a vegetable patch filled with rainbow chards and lush brassicas. Within minutes I hear unfamiliar birdsong which my app identifies as Cetti’s Warbler. Another path loops past an area where the growing beds are curved and heaped to maximise exposure to the sun and then I wander through the Food Forest, taking note of the planting; marvelling at how well the intentional things grow alongside the willows and reeds; admiring the largest rosehips I’ve ever seen; charmed by russet-speckled Nashi Pears dangling from bare branches. There are bug habitats, bird boxes, dead hedges – its my kind of place, and I collect lots of ideas for my various growing projects.

This evening, the International Visitors Programme begins as the group meet for the first time at the hotel with Astrid and Josine, two of our hosts from DutchCulture – we will meet Simon tomorrow. We are well matched – well curated – there is similarity in our situations, challenges and outlook, but also useful differences and places for learning. We have converged on the Netherlands from countries within a train ride of Amsterdam – Evi from Belgium, Alexandra from France, Julia from Germany, Isabel from Spain and me from the UK. Our five countries also fielded artists for a residency programme earlier in the year organised by DutchCulture in partnership with the Netherlands EUNIC cluster. Our programme has been partly shaped in response to these residencies, which were all hosted by Zoöps (a new company structure piloted in the Netherlands which makes space in the company for more-than-human beings through the appointment of a Speaker for/with the Living), and several of our visits this week will be to arts and cultural organisations which were involved in the residency programme and/or have adopted the Zoöp structure.

As we sit and talk, the energy is positive and generous, connections are immediately comfortable, conversation flows. As Evi said later, “it felt like entanglement“.

Tuesday/Day One includes a welcome and overview from DutchCulture’s outgoing director, Kirsten van den Hul; an artist-provocation from Anne Jesuina de Andrade exploring the links between decolonial and regenerative thinking; presentations by each of us visitors to staff at DutchCulture’s shared offices introducing our work and how regenerative thinking influences and manifests in it; a visit to Zone2Source sited within Amstelpark (created for an International Horticultural Expo in 1972 and now evolved into a less managed landscape, gently rewilding itself in places) to meet curator/director Alice Smits; and, finally, dinner at de Ceuvel a ‘playground for sustainable innovation’ where the community of small businesses has worked with plants and natural processes to purify the water and clean the formerly industrial and polluted land.

There is a lot of fruitful conversation, but some things that stick with me:

- The Multi-Species Assembly held at Zone2Source: both the concept of a multi-species assembly (which resonates with me as someone who has organised a Citizens’ Assembly) and the visual impact of the circle of tree stump seats, in a sea of yellow leaves, under the branches and care of the tree-elder that has been allowed to grow to its chosen shape. When talking about the gardener’s provocation to the Assembly, Anna (who is also the Speaker for the Living for Zone2Source) said that “pruning well comes from a place of understanding and connection” – I connect this in my head with the stewardship, wisdom and courage of Kirsten talking about the DutchCulture team’s approach to the government cuts, in deciding to ‘prune’ her post.

- Alice, the Director and Curator at Zone2Source, asked “What is a garden in a climate emergency?” – something I think about a lot! (Solace, resistance, oasis, food, home, respite, cooling, ark, gift, challenge, connection, community, joy, solution…)

- Artists working as researchers (elevating the practice to a more recognised status, appreciating the ways that artists approach research as valuable and effective, just different to academic researchers’ methods).

- Evi speaking of a ‘Wild Card’ approach to selecting residents as a way of getting around having to write, read and reject really great applications.

- de Ceuvel (as one example) proving their worth to the municipality by the way their careful stewardship is actively cleaning the land – taking responsibility for the city’s/planet’s problem with a low-cost creative solution which is also a civic/ecological intervention – and how taking this action brings them and their clientele into closer contact with the wider living world, but also puts de Ceuvel in a position that is both powerful and precarious, depending on whether the municipality embraces them to stay there, or waits until they have cleaned the land and then kicks them out in favour of a business that makes more money. (Classic gentrification move)

- There’s also something about that non-manicured, but healing, land standing as a marker of humanity’s penance – a powerful reminder that we are making reparations for the mess we have made of the world. (This is an idea explored with respect to wind turbines as a blot on the landscape in “Who Owns The Wind” by David McDermott Hughes).

Wednesday/Day Two takes us on a cross-country train journey to Rotterdam and then to Buitenplaats Brienenoord a circularly-built artist-led space on a tidal salt marsh island with a small herd of highland cattle and a pizza oven powered by a sauna; a water taxi back to central Rotterdam; 2 hours of unscheduled time, which I fill with the calming colour and form of a tour round 1930s modernist Sonneveld House; the Zoöp Connections event at Nieuwe Instituut which expands on both the Zoöp concept and the international artists’ residency programme mentioned previously. There are workshops as part of this event: Isabel and I elect to join the lichen-hunting workshop led by artist Fabian Schäfer, who was in residence at de Ceuvel, and spend half an hour closely inspecting the lichen on an elm tree near Nieuwe Instituut – taking photographs through the jeweller’s loupe we have been given to help us observe the lichen close up.

Some things that stick with me from day two are:

- The shifting/cycling of land/water – how the beaver sighting shaped the Brienenoord tidal zone island, and how softening the sheer edges allowed the seeds that were always in the water to wash in on the tide and find a home on the land, creating new habitats.

- Affirmation that other artists also, when they get their hands on a building, spend a while finding its rhythm, its people, what works well, what attracts people, who stays and who only passes through (and this is an echo, for me, of the gasfabriek as well as our work at The Nest).

- Maurice Specht of Buitenplaats Brienenoord asking when an arts organisation becomes an ‘institution’, how can it keep hold of ‘project’ energy? And saying that he will always organise for trust (“don’t build your project around the 2%” of people who want to mess things up).

- Hosting is part of all of our practice(s), but there are questions about how and where we find the balance between generosity and service.

- “The well-maintained path gives intention to the wilderness on either side” (Estelle Zhong Mengual speaking at the Zoöp Connections event)

- Lichen as an apt metaphor for the necessity and benefit of symbiosis, community, reciprocity.

Thursday/Day Three we travel to Utrecht to visit Hof van Cartesius – a collection of units inhabited by small businesses, all of which have been hand built by the community using reclaimed and recycled materials, many sourced from the refurb of the nearby railway station. The units are arranged around courtyard gardens that have been thoughtfully constructed on permaculture principles. We meet with Fabian and Martina of Creative Coding Utrecht, proponents of Permacomputing, an interesting anti-capitalist re-evaluation of our current tech landscapes. We also meet artist Angelina Kumar who is currently researching how deeply felt regenerative action really is within cultural organisations; and we are served a delicious plant-based Asian lunch, made using local and/or seasonal vegetables by food-artist Pao & Tjoy. From there we travel to Nijmegen to visit Eva, Yaniv and Carmen at The Moraine, reflect on our time in the Netherlands and eat more fabulous plant-based food prepared with love and care.

Things from day three:

- Fabian at CCU talking about how policy makers might be moving away from climate policy, but ordinary citizens are moving towards it.

- Martina describing how their Speaker for the Living encouraged them to observe micro-seasons, how this gave rise to deep noticing and how, as they fed their new observations and knowledge into their organisational practice, it became “a kind of embodied folklore”.

- In the exhibition downstairs, we watch plants generate poetry and a film of the Hof’s gardener showing artists and residents the garden, telling the stories of the relationships between plants and insect life, and his efforts to entice frogs to colonise the ponds he’s made.

- The DIY green roof garden has hugelkulture-style layers and is rich with planting and recycled slab paths – there is so much Bistort/Persicaria in flower, and it looks beautiful en masse.

- The importance of gardeners and growers (and the distinctions between these two words).

- ‘Service’ keeps coming up: be ‘in service’, but not ‘providing a service’ – reciprocal, not commercial, relationships.

- Carmen’s seed-catching arts practice – catching the seeds washed down from the Alps by the river Rhine (which resonates with what Maurice told us about the formation of the Brienenoord island) – feels like a parable for life: pay attention to everything that is floating past and create the conditions that allow/invite it to stop and put down roots: to make something here, with us.

Friday: a final candlelit breakfast at the hotel, where we take on the legendary Homeland Breakfast and – while the regular hardy swimmers scoop lengths in the canal wharf next to the historic boats – we say our fond goodbyes. Alexandra, Evi, Isabel and Julia have been the perfect companions to walk alongside these past three days: we have become kin.

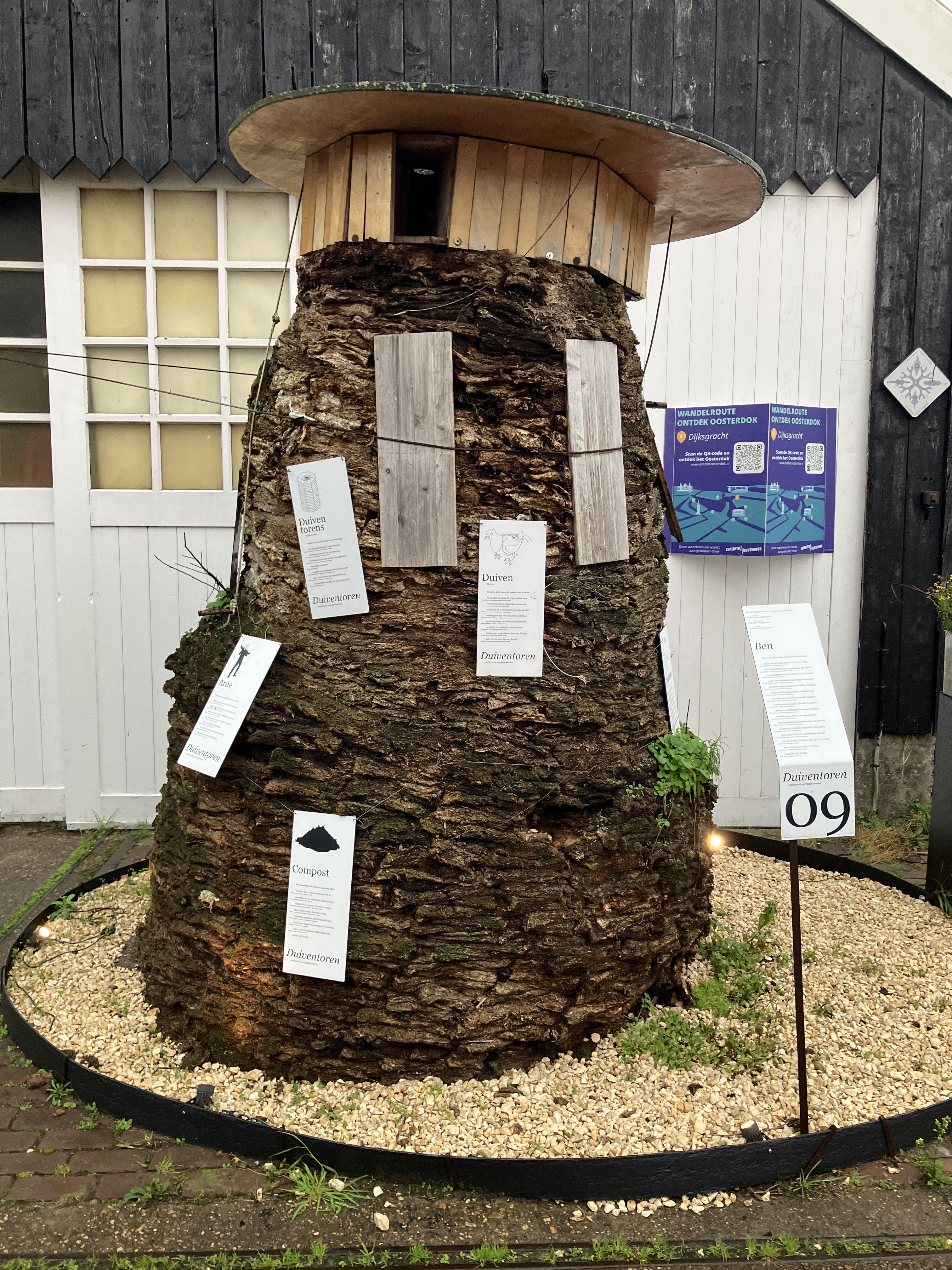

Later, when others have already caught their trains home, I go for a walk round the environs of the hotel, an area I haven’t yet had chance to explore. I find more wilding, more parks and gardens – temporary ones planted in pallet collars and IBC tanks, a testament to people’s determination to just get on and do something to mitigate the collapse, to help regenerate. I see handmade bug hotels and bird/swift/bat boxes attached to industrial warehouses, living walls, towers made of spent mushroom substrate blocks with timber turrets to house wild pigeons – it is wonderful and exuberant and I want to do this. I want to go further than we have already at Talking Birds in thinking about how our practical regenerative actions can support and share space with nature, building stronger reciprocal relations between us humans and our wilder relations, make what’s coming less bad. I want to populate every bit of public space that I can with more green wild-ness, ripping up paving slabs or using inspiration from these DIY pallet collar gardens to give space back to plants and creatures and birds – our wilder kin – and to inspire others to do similarly.

Looking back now, a couple of weeks later, I’m still thinking about the distinction between the words ‘grower’ and ‘gardener’.

In the reflection exercise at The Moraine, I chose to describe myself as a ‘grower’, likening my work to jays or squirrels (hope-fully) planting acorns: some will be dug up and eaten, nourishing someone, but some of the acorns will put down roots, grow into oak trees, flourish and produce their own acorns. It’s a more regenerative analogy than the ‘depth charge’ we used to speak about, but still describes the passing of time, the slow and deep nature of the intervention and the lack of control over its effects and how, or when, they eventually manifest.

For me, then – at The Moraine – ‘grower’ spoke about the way that many seeds/invitations might be issued but there is no measure of the ‘return on investment’ and a high dependence on chance. I’m interested, now, in why I chose ‘grower’ over ‘gardener’ – also a really valuable word. Perhaps I was wary that ‘gardener’ might be associated with highly curated, manicured or controlled spaces – and I didn’t want that association.

But now, I think that what ‘gardener’ gives me – that ‘grower’ perhaps doesn’t – is the element of presence, of tending, and of ongoing care and regeneration. It isn’t stifling or controlling, but it is relational, collaborative, full of reciprocity – and it definitely isn’t about ownership either, but about joyful and mindful stewarding of the precious land, in service to all the users of the garden.

I think back to Alice’s question on day one: “What is a garden in a climate emergency?”

And I think that perhaps my answer is “Everything”.

Huge thanks to DutchCulture, and especially Astrid, Simon, Josine and Kirsten for the invitation, the care, and for curating this new family so thoughtfully. Special thanks to Alexandra, Evi, Isabel and Julia for the conversation, insights, reflections and entanglement.

I was really inspired by my visits to Rotterdam and Amsterdam – organised for me by Maurice Specht, oddly enough, who I’ve lost touch with. I remember walking and meeting a little older lady, with a hammer and an old screwdriver, pulling up the small, square slabs outside her home to plant flowers, and thinking what a different spirit that was. And in a final looping-in, I remember thinking that Rotterdam and Coventry felt quite similar, somehow. Look forward to what comes next.

Small world, eh? I remember going to hear someone from Rotterdam speak about the ways they were adapting, updating and reinventing their post-war building stock – ways that Coventry might learn from!